Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand and Wrist

Every patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) of the hand and wrist is different. The patterns of stiffness, pain, swelling, and deformity are as individual as fingerprints. That uniqueness is exactly why, as a plastic surgeon with a special love for the hand and wrist, I was drawn into this field. The hand is a beautiful piece of engineering, and rheumatoid disease asks some very hard questions of that engineering.

I sometimes joke that if you want the job done right, ask an orthopaedic hand surgeon – but if you want the right job done, ask a plastic surgeon. Underneath the humour is a serious point: in rheumatoid arthritis, the art is choosing just enough surgery, in exactly the right place, to give you the biggest improvement in your life with the least possible disruption.

For many decades, RA of the hand and wrist was synonymous with severe deformity: fingers drifting towards the little finger (ulnar deviation), thumb in a zig-zag “Z” posture, joints dislocating and collapsing, and wrists that gradually lost all alignment. In that era, minimalism simply wasn’t an option; by the time patients reached a surgeon, the disease had often mutilated the hand.

Figure 1. Severe long-standing rheumatoid arthritis with marked deformity and joint destruction. Modern medical treatment means this degree of damage is now much less common, but it illustrates the extreme end of the disease spectrum.

The story today is very different – and that’s the first piece of good news. Modern disease-modifying drugs and biologic therapies (immunomodulators) have dramatically reduced the rate of severe joint destruction in RA. People are diagnosed earlier, treated more aggressively, and, as a result, far fewer will ever develop the extreme deformities that were once common.

But “far fewer” is not “none.” I still see patients with difficult pain, progressive deformity, tendon ruptures, or collapsing wrists. I’ve also met many people – including my own grandmother – whose hands looked profoundly deformed yet who quietly carried on with their daily lives and never felt the need for major surgery. So the challenge is not “Can I operate?” but “Should we operate – and on what, and when?”

This page is here to help you understand the options for rheumatoid arthritis in the hand and wrist, and how I think through those decisions with you.

What rheumatoid arthritis does to the hand and wrist

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease. Your immune system, which is supposed to protect you from infection, mistakenly attacks the lining of your joints (the synovium). That lining becomes inflamed, thickened and overactive. Over time, the inflammation can erode cartilage, bone, ligaments, and tendons.

The hands and wrists are among the most commonly affected areas. RA often starts in the small joints of the fingers and wrists, and it tends to be symmetrical – the same joints on both sides are involved.

Typical changes you may hear about include ulnar deviation (fingers drifting towards the little-finger side of the hand), “windblown” hand deformity, swan-neck and boutonnière deformities of the fingers, thumb “Z” deformity, and collapse or erosion of the wrist and the joint between the radius and ulna (the distal radioulnar joint). These deformities develop because tendons slip out of their normal grooves, ligaments stretch, and bone is gradually eroded by inflammation.

Modern medication – and what surgery is for

Today, the cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis treatment is medical. Conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) like methotrexate and newer biologic agents targeting specific parts of the immune system have transformed the outlook for many patients. These medications do not cure RA, but they slow it down, reduce pain and swelling, and – crucially – prevent or delay joint destruction. As rheumatologists have used these drugs earlier and more aggressively, several large studies have shown a decline in major hand and foot surgery for RA over time.

So where does surgery fit in now? In broad terms, surgery in rheumatoid hand and wrist disease is about reducing pain that no longer responds to medication, correcting deformity that stops you doing important tasks, preventing or managing tendon ruptures and nerve compressions, and rebalancing the hand so that the joints that are still good can work more efficiently.

The goal is not to give you a textbook-perfect X-ray. It’s to help you function, with your actual life, values, job, hobbies, and tolerance for risk and recovery time. The plan for a concert pianist, a mechanic, and a retired gardener with the same X-ray will probably be very different.

My general philosophy: least intervention, greatest effect

Rheumatoid arthritis tempts surgeons into “big” operations because the deformities can be dramatic. Historically, it wasn’t unusual for patients to undergo multiple staged reconstructions: tendon transfers, joint replacements, wrist fusions, thumb realignment – sometimes all in one limb. Those operations still have a place, but I try to approach things a little differently.

We start with what bothers you most: is it pain, strength, appearance, or a specific task you can’t perform? We then look for small, targeted surgeries that unlock big improvements, always respecting the biology of rheumatoid disease. RA affects ligaments and soft tissues, so we don’t always get the same predictability of healing as in osteoarthritis or trauma. We also plan surgery around your medication, balancing the infection risk of continuing drugs with the risk of a flare if they are stopped.

Sometimes the right choice is no surgery at all, but better splinting, hand therapy, and medical care. Sometimes a single focused procedure, such as straightening and fusing one painful joint, makes your whole hand feel more reliable. And sometimes, in more advanced cases, “salvage surgery” – major tendon and joint reconstruction – really is what gives you back a usable hand.

The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints – the “knuckles”

In rheumatoid disease, the MCP joints – the big knuckles where the fingers meet the hand – are often major troublemakers. As the supporting ligaments and tendons are damaged, the MCP joints can slide partly or completely out of their sockets, drift toward the little finger, and in severe cases allow the fingers to “telescope” back into the hand.

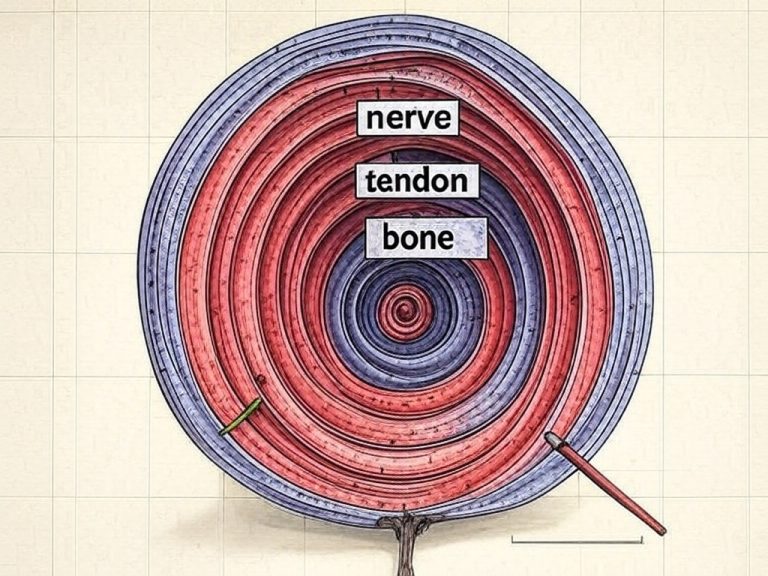

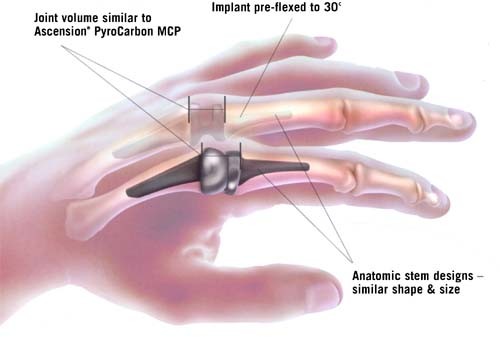

When pain is severe and the deformity is fixed, we often talk about MCP joint replacement (arthroplasty). Silicone implants have been used for decades in rheumatoid MCP joints. They act more as a flexible spacer than a true hinge.

Silicone arthroplasty can reliably reduce pain, straighten the fingers, and bring them back over the metacarpal heads. It often improves the ability to open and close the hand for light to moderate everyday use. What it cannot do is restore a completely normal joint or tolerate heavy gripping and impact activities. Over many years the implants can fracture or allow some recurrence of ulnar drift, but for the right patient they can be life-changing.

For more isolated MCP arthritis, particularly in osteoarthritis or psoriatic arthritis, we sometimes consider pyrocarbon joint replacement. Pyrocarbon has mechanical properties closer to bone than metal and can provide an anatomic-looking joint replacement. It offers good pain relief and motion for many patients, but it also has its own potential problems, including instability, loosening and the possibility of further surgery if the implant fails. It is not a “better silicone,” just a different tool that must be matched carefully to the right patient.

Figure 2. Illustration of a pyrocarbon and a silastic metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint replacement in the finger.

Figure 3. Example of a pyrocarbon joint implant used in selected hand joints.

Figure 4. X-ray views of pyrocarbon joint replacements in small finger joints.

The interphalangeal joints – middle (PIP) and tip (DIP) joints

The joints in the middle (proximal interphalangeal, or PIP) and at the tip (distal interphalangeal, or DIP) of the fingers are frequently involved in RA, but they behave differently.

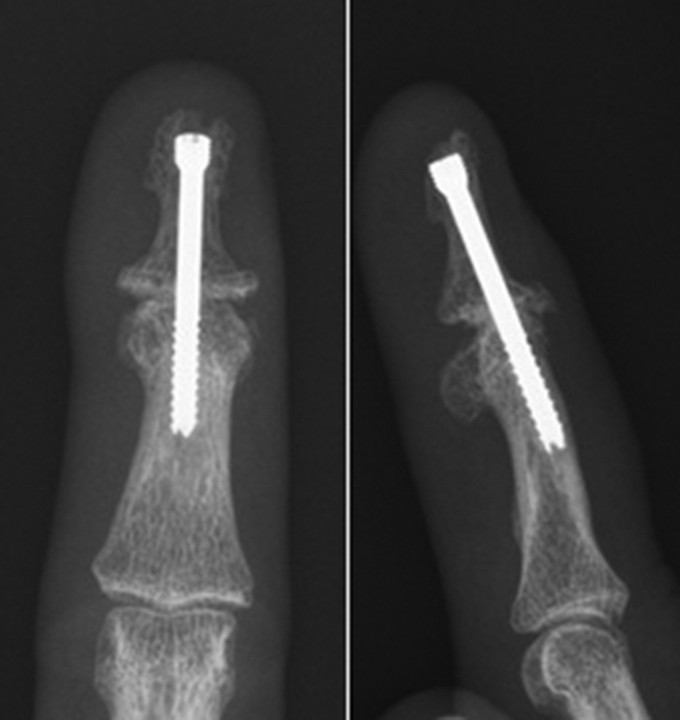

The DIP joint is biomechanically forgiving. For most people, fusing this joint straight or with a small bend does not noticeably affect function – you can still make a fist, grip tools, and type. So if a DIP joint becomes a small, concentrated source of pain from RA or secondary osteoarthritis, fusion (arthrodesis) is often an excellent, durable solution. The trade-off is simple: no motion, no pain.

Figure 5. X-ray showing fusion of the terminal finger joint (DIP joint) using a compression screw.

The PIP joint is another story. It is crucial for making a fist and for fine handling. Losing motion here has a much bigger functional cost. There are two main surgical ideas: joint replacement (arthroplasty) and fusion. Pyrocarbon and other implants have been used to replace the PIP joint in RA and osteoarthritis, but real-world outcomes have been mixed, with relatively high rates of complications and revision surgery. For that reason, I do not routinely offer PIP joint replacement. Instead, I reserve PIP fusion as a surgery of last resort for joints that are both very painful and functionally useless.

Injections: steroid, hyaluronic acid, and fat

Over the years I have watched (and performed) hundreds of small-joint injections. They are tools, not cures. Steroid injections can quiet inflammation and give good short-term relief, but in many people the effect fades in a matter of weeks or months, and repeated injections may have diminishing returns. Hyaluronic acid, a lubricating gel, has been tried in small joints with mixed and often modest benefit.

Autologous fat injection (lipofilling) has gained interest, particularly for basal thumb (carpometacarpal) arthritis. In these procedures, a small amount of your own fat is harvested, processed, and injected into the affected joint. Clinical studies in basal thumb osteoarthritis show that fat transfer can reduce pain and improve function in a majority of patients, especially in earlier stages of disease. I have also injected fat into finger joints in selected patients. It does not cure the arthritis, but it can make the joint more tolerable – turning down the volume on the pain and sometimes delaying the need for fusion.

The wrist and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ)

The wrist is a central player in RA. As the carpal bones and the ends of the radius and ulna are attacked, the wrist can lose its normal architecture, collapse, and become both painful and unreliable.

There is a spectrum of surgeries, ranging from relatively conservative to definitive fusion. These include synovectomy and tendon procedures to remove inflamed synovium and protect tendons; partial fusions or proximal row carpectomy to preserve some motion while stabilising the wrist; and total wrist fusion to create a strong, stable platform for grip in the most severely damaged wrists. Total wrist fusion sacrifices wrist motion but can be extremely effective at removing pain.

Figure 6. Dorsal plate used for total wrist fusion, creating a stable, pain-free wrist in advanced rheumatoid arthritis.

The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) is where the radius and ulna meet at the wrist. In RA this joint can erode badly, causing pain, instability, and difficulty rotating the forearm (turning the palm up and down). Traditional operations remove part of the ulna or fuse portions of the joint. In selected patients whose DRUJ is the main problem and whose surrounding structures are suitable, I may recommend an implant such as the Aptis prosthesis – a specialised device that replaces the DRUJ while preserving rotation. This is a very successful but relatively rarely indicated option that requires careful patient selection.

Figure 7. X-ray showing an Aptis distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) prosthesis used to restore forearm rotation.

Tendon rupture and tendon transfer

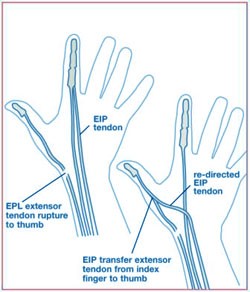

Because rheumatoid arthritis attacks not just bone and cartilage but also the tendon sheaths, tendons can fray and eventually rupture. This is particularly common in the extensor tendons on the back of the wrist and hand. When a tendon has ruptured, no amount of splinting or medication will restore its function; the mechanical connection is lost.

In these cases, we often borrow a healthy tendon and re-route it to take over the job of the ruptured one. A classic example is transferring the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) tendon, which normally helps extend the index finger, to replace a ruptured extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon that extends the thumb. Most patients hardly notice the loss in the index finger, but they regain active extension of the thumb, which is crucial for grip and pinch.

Because functional tension testing is so much easier when the patient is awake and voluntarily following commands, I offer tendon transfer under local anesthetic often in the office procedure room.

Figure 8. Diagram of an extensor indicis proprius (EIP) tendon transfer to restore thumb extension after EPL rupture.

Splinting and rehabilitation

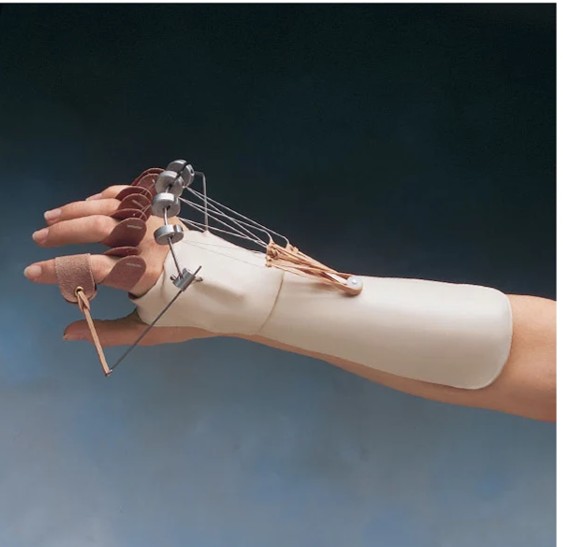

After joint replacement or tendon reconstruction, splinting and hand therapy are absolutely central to a good result. The soft tissues in a rheumatoid hand are often stretched or weakened by inflammation, so they need external support while they heal in their new position.

In addition to resting hand splints, we may use dynamic “outrigger” splints. These use elastic bands attached to a light frame to guide the fingers into better alignment while still allowing gentle active movement. For rheumatoid patients, this external rubber-band system can be the difference between a stable, straight hand and a gradual relapse into deformity.

Figure 9. Dynamic outrigger splint used after joint reconstruction to maintain finger alignment while allowing controlled motion.

What to expect from surgery and recovery

Every operation described here is just one step in a larger journey. For rheumatoid patients in particular, success depends on close coordination with your rheumatologist regarding the timing of DMARDs and biologic drugs around surgery, expert hand therapy to retrain tendons and protect reconstructions, splints and braces that may be worn for weeks to months after surgery, and realistic expectations about what surgery can and cannot do.

In practical terms, many procedures can be done under regional or local anaesthetic, often as day-surgery. Pain after surgery is usually manageable with a combination of elevation, simple painkillers, and nerve-friendly anaesthetic techniques. Regaining confidence in the hand can take time; it’s not just about wounds healing, but about learning to trust the new mechanics.

I will be very honest with you about likely outcomes. A fused joint will not bend. A silicone MCP will not tolerate heavy labour. A wrist fusion will not let you do traditional push-ups. But if these procedures remove a constant source of pain and give you a hand you can rely on, they can be extremely worthwhile.

Pulling it all together – your hand, your life, your choices

When I look at a hand with rheumatoid arthritis, I don’t just see deformity; I see the story of how that person has adapted over time. I have seen patients with extreme ulnar deviation and telescoping fingers who can still cook, dress, garden, and even play music – just as my grandmother did, with profound deformity but remarkable function.

So the central question is always: what do you want your hand to help you do that it can’t do now? For one person, that is picking up a grandchild without fear of dropping them. For another, it is holding a paintbrush, getting back into the workshop, or simply shaking hands without flinching.

Modern RA medications have spared many people from the most severe damage, but there will always be a role for thoughtful, tailored hand and wrist surgery. My job is to listen to your story and priorities, examine not just your X-rays but how you actually use your hands, and offer you the smallest, smartest surgical or non-surgical steps that move you towards your goals, while being honest about limitations, risks, and recovery.

If you live with rheumatoid arthritis in your hands or wrists and you are wondering whether surgery might help, the answer is almost never a simple yes or no. It is a conversation. That conversation starts with you bringing your hands, your questions, and your goals into the room. From there, together, we can decide whether the right thing is splinting and therapy, a precise injection, a carefully chosen joint fusion or replacement, or – quite often – a decision to leave a remarkably adaptable hand alone.