Thumb base arthritis

There is one thing I tell my patients that might seem a little odd: “The graveyards are full of people who died with thumb arthritis that they never had surgery on.” But let’s get to the start of the story.

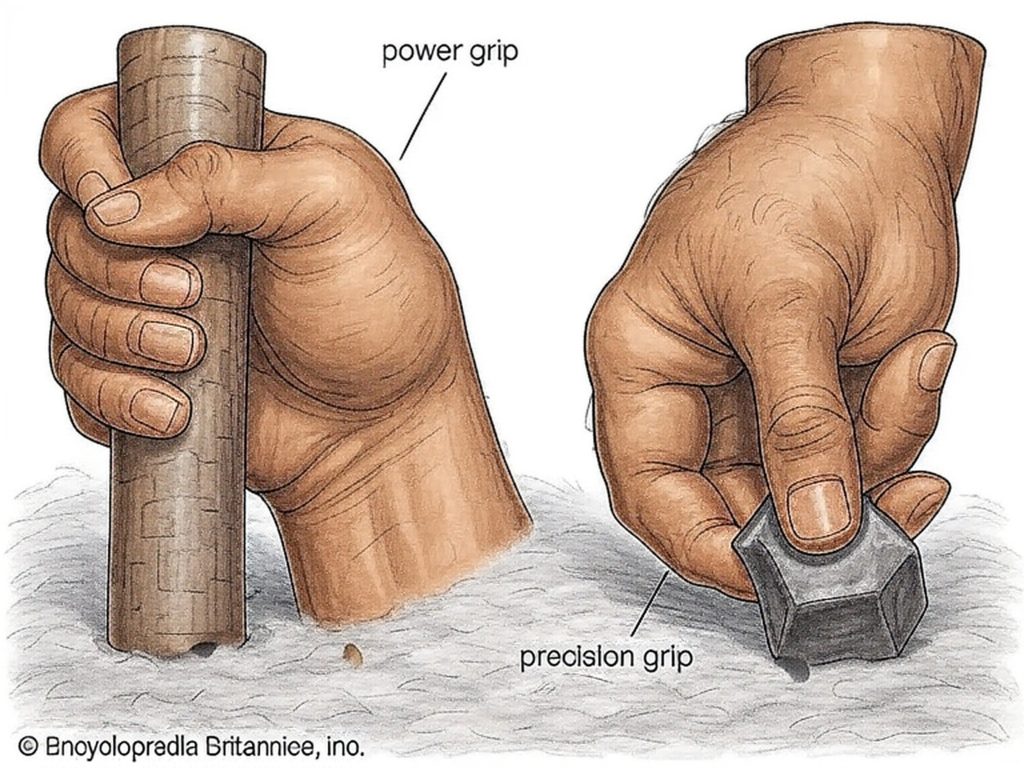

The human hand manifests an elaborate joint architecture around our tool use, requiring the thumb to not only flex and extend and move across the palm but also rotate, to oppose each finger in plane. Most joints in the body have stability as their key feature, allowing motion in a more limited range of planes, but there is a trade-off.

Somewhere between our late 40s and mid-60s, most of us start to develop osteoarthritis of this joint, which is hypothesized to be as a result of “wear and tear,” although the causes for joint degeneration are likely to be a very mixed bag of ligament laxity due to the slowing of our repair mechanisms, and subsequent inflammation that erodes the cartilage, which cannot regenerate. This is in addition to the more rare autoimmune diseases that I will cover in a different blog.

Characteristically, basal joint arthritis afflicts more of us than any other upper limb arthritis, probably because of this vulnerability. So when do you “need surgery”? The answer lies in the balance between the amount of disability the pain inflicts on your everyday use of the hand, and the individual’s preparedness to go through a surgical procedure that may take 3 months of hand therapy until it fully bears fruit. Call this the line in the sand.

Before I break down the options, I want to share a story.

My own mother, a retired operating room nurse dead set against all non-essential surgery, chose to have a basal joint arthroplasty. Subsequently, she has avoided almost all of the classic orthopedic operations, and her left knee at the age of 86 is crooked—and has been for over 10 years—for which she was simply not prepared to have surgery. The thumb issue for her was personal: she lost her tennis serve at age 72, which was at the heart of her local social life. As I put it to my patients, she had reached a line in the sand that she was not prepared to cross. As we age, we accommodate to many, many changes—some are tolerable, and others intolerable. This is the line that any individual must cross to make the elective decision to have surgery to enhance their form and function through plastic and orthopedic surgery. Use this as a good guide to help make choices from the following options.

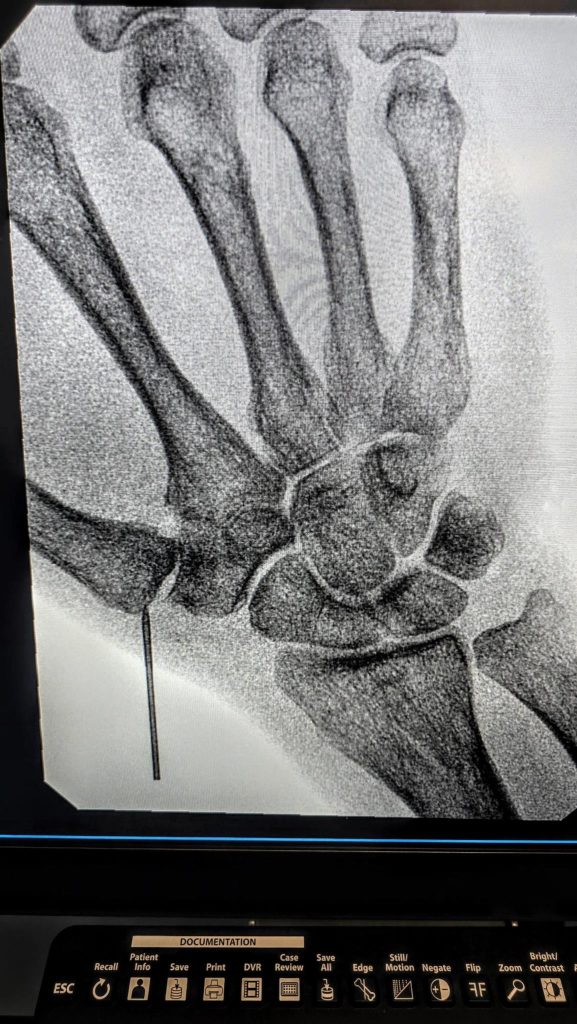

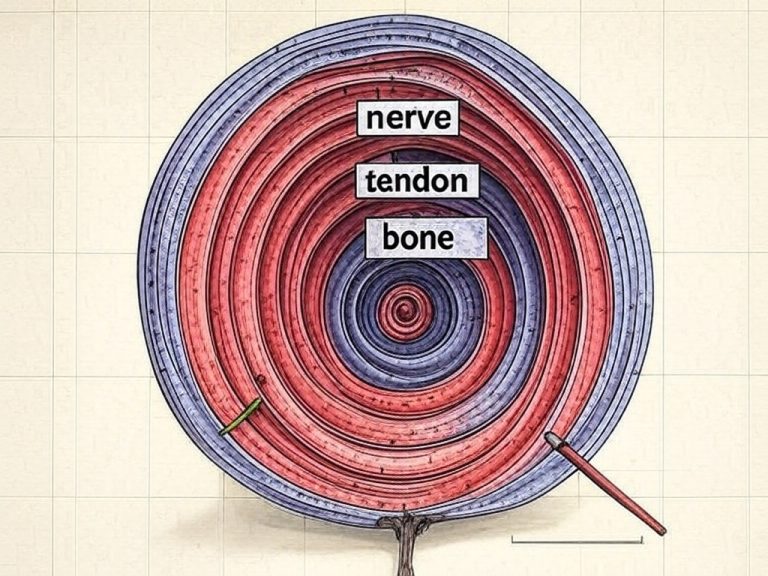

Rule out simple causes for pain: Before considering your basal joint to be the cause for your pain, I need to exclude both nerve and tendonitis issues that may be masquerading as joint pain, or simply enhancing it, see my blog on the onion skin model for hand pain.

Initially, basal joint arthritis is managed by hand therapy using small braces that help stabilize the joint, called “Opponens bracing”. This gives you the opportunity to speak to a hand therapist about recovery from surgery and to meet other patients who have had surgery, and it may well be enough for you.

Injections:

I was always trained to offer steroid injections into the joint. I have the advantage of a 15-year training period between the UK and the US, and I was able to observe the white crystalline material that these steroids deposited in the soft tissues when we did surgery. I began to wonder about the effects of steroids, because so many patients appeared to be attending clinics regularly just to have injections that wore off. The steroids used to inject tendons and joints are “catabolic,” meaning they break down inflammatory and collagen tissue as part of their direct action. The initial experience is beneficial, but as the ligaments that are so important to basal joint stability are weakened, I always had the impression that only harm could follow. And given that steroids into joints seemed to wear off over months, I stopped offering them (although they are often effective permanently for tendon issues). For years, it was either hand therapy or surgery that I offered.

As a plastic surgeon, I have worked with fat transfer, particularly in breast reconstruction, and in addition to seeing it first hand I was aware of the literature demonstrating the beneficial effects of fat on tissue that was hard and scarred subsequent to surgery plus radiation. I also observed that when I injected fat beneath scars, they tended to mature and soften, sometimes almost melting away. Then a connection was made in my mind when I read a German study that demonstrated fat transfer into the basal joint was reducing pain for 2–5 years. This seemed totally unsurprising to me, and so immediately I began to offer fat injection into the basal joint, which had the added advantage of something I could offer in the office environment, away from the industrial hospital complex. I have been offering this since late 2022, and about 70-80% of my patients report significant reduction in joint pain by 3 months, and some of those who don’t then go on to improve by 12 months. When I see them a year later, not only has this held true, but the effects seem to have increased. Whatever is going on with fat transfer, it is an “anabolic” phenomenon and appears to be improving overall joint health. There is an emerging science in this regard, and companies are racing to enrich fat with stem cells or to inject alternative sources of stem cells from bone marrow. One thing we don’t know is a fair comparison between techniques, and I prefer to keep it simple between me and the patients: we just harvest a little fat from the tummy under local anesthesia, and it’s working.

There is another technique that may be offered before arthroplasty, which I have not yet adopted, “Denervation” of the joint, which carries some promise. It does however involve an extensive dissection of the soft tissues to remove nerve branches that enter the joint capsule. I have yet to adopt it due to the early data available, the fact that arthritis proceeds unchecked and that it is considerably more traumatic than fat transfer. I also know that nerves regrow, so I remain a skeptic until longer term data is produced. Basal Joint suspension Arthroplasty with trapeziectomy:

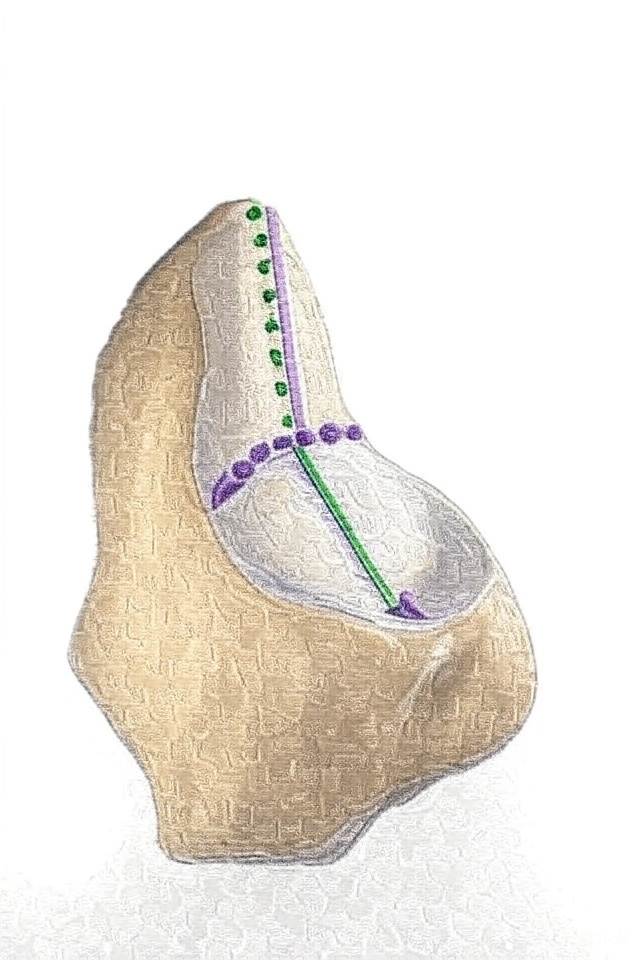

The next step up the ladder is a “basal joint arthroplasty.” Traditionally, the trapezium bone under the thumb where the arthritis is found, is simply removed, and time and again clinical trials have failed to show that any other technique is superior. How the trapezium is removed is fairly traumatic, however, and recovery for the first 2–6 weeks significantly limits the use of the hand, permitting typing but little else. The problem that surgeons first encountered after this operation was that the thumb would sink back into the space left behind by the removed bone, eventually causing new arthritis on the next bone in the chain, the scaphoid. So elaborate and varied techniques have evolved to “suspend the thumb”. I have done or assisted in most of these procedures over the past 30 years and currently I have chosen to use the Arthrex FiberLock system with a single incision, again aiming for simplicity—it permits early motion at 2 weeks. Others will offer a variety of tendon graft and transfer techniques, most commonly the “LRTI,” which is a tried-and-tested workhorse requiring immobilization for 4–6 weeks.

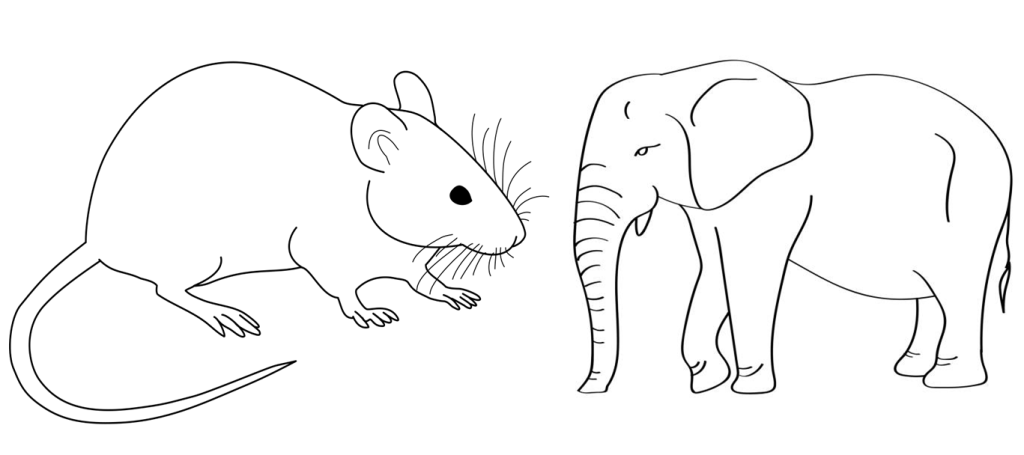

Implant arthroplasty: In the UK and the US, we have had many decades of resistance to thumb implant arthroplasty after a series of bad outcomes from various designs. Designing an implant that can support the loads placed through them is intrinsically more predictable when the surface area to volume ratios are small. By this, I refer to the overall size of the implant and the bone in which it must integrate. A knee joint may look like a finger joint, but it is not at all. It’s an optical illusion best explained by the comparison between an elephant and a mouse. A photograph of each shows a rather plump round body, and they appear analogous to each other.

The brain is failing to grasp that the surface area to volume ratio is drastically altered between the two: with the mouse being small, it has a relatively small volume for its surface area, versus the elephant, which has a huge volume, so the volume to surface area ratio is many orders of magnitude smaller. For the dynamics of a small implant versus a large one, this translates into instability, loosening, or dislocations. Thus, when hand surgeons have enterprized into small joint arthroplasty, we have not replicated the great success we see in hips and knees. One of the best examples was seen around the 1980s with Dr. Alfred Swanson in Grand Rapids, who developed a multitude of small implants, most of which had to be removed over the ensuing years. It was thus with distrust that Britain and the US viewed the promising data emerging from France, Belgium, and the Netherlands about implant arthroplasty of the basal joint, but enthusiasm is rising once again. In the US, we have access to a one-sided implant.

I have been offering the BioPro, a Michigan-invented and manufactured implant—like Swanson, so the story has stayed local. Coming soon through the FDA is a two-part implant from Europe, which in their studies has shown great promise. What I tell my implant patients is that the BioPro is a little less traumatic and painful to place: the trapezium remains, so the arch of force is supported bone to bone when pinching, one of the fundamental functions of the thumb. Losing the trapezium arguably weakens the hand a little; the implant helps maintain strength. But I remind my patients that an implant is not necessarily the last operation that they will need, and later in life it may loosen or dislocate. Nevertheless, particularly for younger patients, the implant has a role, and so I offer it.

Summary:

Fat Transfer: Minimally invasive procedure harvesting fat from the abdomen under local anesthesia; provides anabolic benefits like pain reduction in 80% of patients within 3 months, potentially lasting 2-5 years with improving joint health; ideal as a non-surgical step-up from bracing, avoiding bone removal or implants, but lacks long-term comparative data against other methods.

Trapeziectomy: Traditional surgical removal of the trapezium bone, often combined with suspension techniques like Arthrex FiberLock (allows early motion at 2 weeks) or LRTI (requires 4-6 weeks immobilization); effective for severe cases but involves traumatic recovery limiting hand use for 2-6 weeks, with risks of thumb subsidence leading to new arthritis; no superiority shown over simple removal in trials.

Implant Arthroplasty: Uses devices like BioPro to replace joint function while preserving the trapezium for better strength and bone-to-bone support during pinching; similar recovery times to but less traumatic than trapeziectomy, suited for younger patients; however, carries risks of future loosening or dislocation, possibly requiring additional surgeries, and has historical distrust due to past design failures.

Conclusion: Remember, I started this blog with the macabre image of skeletons still carrying their trapezium bones to the grave. Its your life, and only you can know if you have reached a “line in the sand” beyond which you are not willing to go.